Due to the popularity of the previous article in this series, we present you with a real life example recorded during One Shepherd’s Fall 2015 field training exercise (FTX). The video was recorded in an S-250 communications shelter. It houses the radio/telephone operator (RTO) equipment used by the tactical operations center (TOC). In this specific example, it depicts a conversation between a team and higher command.

Communications Breakdown: Part 2

In Part 1 of this series, we framed the SOI as to its use and focused on the portions that do not involve a radio. Building upon that knowledge, we’ll discuss Call

Signs, Encryption Code/Authentication Tables, and Brevity Codes. Each of these is a must when communicating over a radio in order to keep your message ambiguous to any unwanted listening ear.

Call Signs:

In most circumstances, call signs are designated by an alpha-numerical group. For instance, in the above example “Y44”, pronounced “Yan-kee Fow-er Fow-er”, represents Higher Command. You will notice that for Squads 2-4 there is no letter assigned to them. This is because they all share the same designation of “B” or “Bravo”. In this situation all squads are represented by “Bravo” and designated by their different numbers. If I wanted to contact Squad 4 I would use the call sign “B22” (Bravo Two Two). Without getting too far into radio etiquette, when we want to contact someone we will say their name twice and our name once as seen below:

“Yankee Four Four, Yankee Four Four, this is Bravo Two One, OVER.”

Encryption Code/ Authentication Table:

This portion serves two different functions: Coding numbers and Authentication. To represent the numbers 0-9, we tend to use a single ten letter word with no repeated letters such as “Binoculars”. You can use a combination of words as long as it totals ten letters and does not repeat any of the letters between the two words as seen above with “Dumbwaiter”. In fact, the authentication table can simply be a combination of ten random letters; however, use of random letters makes memorizing the authentication table extremely difficult.

In the event that you believe someone is using your radio frequency that should not be using it (i.e. – you do not recognize the other person’s voice), you should request an Authentication to make sure they are who they say they are. The Authentication can change with every SOI or can be set as a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) by the unit. In this case, the table states that the Authentication is “2 right”. This means that when someone requests an Authentication, you will move two slots to the right and return the letter and number. It will look something like this:

“Bravo Two One, Authenticate ‘Whiskey’, OVER”

“Yankee Four Four, I Authenticate ‘India Seven’, OVER”

You will notice that Higher requested authentication of “W”. From there we moved two positions to the right (2 right) and answer, “I-7”. As stated before, this authentication can be changed with every SOI or can be set in stone. The important thing is that EVERYONE is on the same page with what the authentication process is.

Brevity Codes:

As stated above, SOI can be much more comprehensive. Next we will discuss organization and use of an SOI. Below we see some examples of things you may wish to communicate in a secure manner.

Above are two categories; REQUESTS and SITUATION REPORTS (SITREP). Each message that we wish to send is on the left side of the columns while the code word it corresponds to is on the right side of the columns (i.e. – Situation Report = COLLAR). You will notice that within each category, all of the code words begin with the same letter. This is the chosen organizational method for this specific example. While organizing the categories’ code words is not required, it does make decoding significantly faster. This is due to the fact that if one hears a word that starts with “A” then they know to look under the SITREP column. The best way to understand how to use the SOI is to analyze a few examples.

For instance, let us say Higher Command wants to know where you are in your mission and what you are doing. They would be asking for a Situational Report (SITREP) and you want to tell them that you are at your Objective Rally Point (ORP). With Higher Command in BOLD and you in Italics, the radio traffic would look something like this:

Coded Message:

“Bravo Two One, Bravo Two One, this is Yankee Four Four, OVER”

“Yankee Four Four, this is Bravo Two One, OVER”

“Bravo Two One, message follows, OVER”

“Yankee Four Four, send message, OVER”

“I send, COLLAR, how copy. OVER”

“I copy COLLAR, OVER”

“Good Copy, Over”

“Wait one”

“Yankee Four Four, I send ARMAGEDDON, ARROGANT, ANSWER, how copy, OVER”

“I copy ARMAGEDDON, ARROGANT, ANSWER, OVER”

“Good Copy, OVER”

“Understood, Yankee Four Four, OUT”

Decoded Message:

“Bravo Two One, Bravo Two One, this is Yankee Four Four, OVER”

“Yankee Four Four, this is Bravo Two One, OVER”

“Bravo Two One, message follows, OVER”

- Higher is giving you a heads up that they are about to send a message so that you can get your writing materials ready to copy the message.

“Yankee Four Four, send message, OVER”

- Once you are prepared to copy the message, you tell Higher to send the message.

“I send, COLLAR, how copy. OVER”

“I copy COLLAR, OVER”

“Good Copy, Over”

“Wait one”

- We decode to find out that COLLAR means SITREP. They want a Situation Report

- At this point we want to send that we are “Halted in our Objective Rally Point”, thus we use the codes for Halted, In/At/On, ORP

“Yankee Four Four, I send ARMAGEDDON, ARROGANT, ANSWER, how copy, OVER”

“I copy ARMAGEDDON, ARROGANT, ANSWER, OVER”

“Good Copy, OVER”

- Higher command decodes the message and understands that the patrol is in their ORP. Then sends:

Understood, Yankee Four Four, OUT

As you can see, Higher Command just got a real time situation report from a patrol in a secure manner. Even if the enemy was listening to the transmission, they would have no idea what was being communicated; unless of course they had one of our SOI’s. You will also notice that each time a coded message is sent, it is “copied” by the receiver to ensure that they heard the correct word over the radio. This seems redundant; however, this is the procedure used to ensure that communications are proficient and conveyed correctly. It is simply a procedure to make sure you are decoding the correct information and not recording the wrong code word, adding unnecessary confusion to your communication. Now, it is also important to understand that at times, these messages can be expedited as well. When communicating with someone who is familiar, certain steps can be skilled in order to speed up the communication. This is beneficial as it reduces the “time on the net” which in turn makes it more difficult for the enemy to triangulate your position, should they have the equipment to do so. That, however, is beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion

An SOI can be as comprehensive or as simple as the mission requires. The important thing is that you have the ability to communicate securely and efficiently. Although technological advancements have allowed today’s militaries to encrypt communications, it is important to understand that technology fails. Yes, you may have a fancy GPS, but you should not solely rely on this equipment. You still carry and remain proficient with a map and compass. The same is true with this form of communication. Regardless of the manner chosen to communicate, the ability to communicate effectively can often times be the essential factor between success and failure. Over my many years of experience in One Shepherd, I cannot think of a single AAR that did not have communication come up as something to improve on. Communication is a force multiplier. Setting up lines of communication, establishing a communications SOP, and securing messages through efficient use of SOI can help any team communicate masterfully. These competencies in communication can be translated to any team, unit, project group, or leadership position. Good leaders acknowledge this fact and continuously seek to communicate more effectively.

Doing It All Over Again

“If I had it to do all over again”, or, “If I had only known then what I know now”… how often have you heard those sentiments, or perhaps even expressed them yourself? The lessons we learned in the “school of hard knocks” have become engraved on our brains in a way that no classroom lecture ever can. Yet, the trouble with learning by experience is that some endeavors are so costly in failure, that the student never gets a second chance to benefit from his mistakes. War is certainly such an endeavor. How many Alexanders and Napoleons might the world have known if only they had not died in their first attempt at battle? The sci- fi film, Edge of Tomorrow, postulates just such a scenario. In the film, Private Cage, played by Tom Cruise, is repeatedly killed in battle, only to be resurrected again just hours before the battle, to relive the events again. In the film, Cage begins as a bumbling idiot; however, contrary to Heraclitus, he treads in the same river again and again, each time benefiting form the lessons he learned previously, and eventually emerges the consummate warrior. I won’t spoil the plot for you by telling whether or not he single- handedly wins the war, and the heart of the pretty girl. All well and good in fiction, but until we find a way to resurrect departed soldiers, we must find a different way to train.

Early in the 1960s, Colonel John Boyd, a USAF fighter pilot, tried to determine the secret of successful fighter pilots. He devised the now- famous O.O.D.A. loop, with O.O.D.A. standing for Observe, Orient Decide and Act. The pilot first observes the enemy aircraft, orients himself to said aircraft, decides how to engage (or not) the aircraft, then acts on that decision. It is called a loop, because as the pilot’s action will have an effect on the enemy aircraft. He then starts over again, observing the effect, re- orienting to the enemy, deciding a new course of action, and acting. Boyd found that the pilot who could cycle through that loop faster than his adversary prevailed.

The problem with Boyd’s O.O.D.A. loop is that it is a little bit like saying, “to win a football game one must score more points than one’s opponent”. It describes accurately what must happen, without explaining how to bring it about. Most attempts at describing the ‘how’, have done so by inserting a series of flow charts between the steps of O.O.D.A. It is as if the pilot is flying along with a series of simple plans in his mind; ‘if I observe the enemy in front execute plan A, if he is above me plan B, if behind me plan C’ , etc. In practice, the flow chart method for an Infantry man might look something like this:

Imagine a foot patrol is tasked with clearing a route; say, for example, a logging road through the woods. Along the way, the point man Observes that he is taking fire. He furthermore Observes that the people shooting at him are indeed wearing enemy uniforms. He then Orients himself to the enemy using the flow chart. Is the enemy closer than hand grenade range? Yes? No? Are there any barriers between him and the enemy? He decides the answer to both questions is yes; therefore, he decides to direct the squad to assault through the ambush. Having made that decision, he Acts on it. He then Observes the result, starting the process over again.

This is all well and good for developing a classroom understanding, but flow charts are too cumbersome for critical decisions that must be made instantaneously. The above- described squad would be annihilated by any halfway- skilled enemy, before the point man made it to the decision part of the process.

Enter a contemporary researcher, Gary Kline, who studied firefighters and neonatal nurses, among others, to understand how people make important decisions under pressure of time. He found that these professionals, and others like them, based their decisions, not on any flow chart, but on past experience. One example he outlines is of a firefighter, who must rescue a woman hanging on a ledge over a busy freeway. Based on his past experience, he knows he does not have the time stop traffic and reach her with a ladder, and so decides, also based on experience, that he can lower a rescuer on a rope from above. It is noteworthy that the firefighter in this story went through the O.O.D.A loop process, he just did not use the flow chart method of decision making; rather he recognized similarities to his past experience, and acted upon those experiences. Kline calls this “recognition primed decision making”.

Let’s look at our infantry patrol above, from a recognition based decision making model. The point man begins leading his patrol along the logging road, as his orders prescribe. As the patrol travels down the road, it becomes more and more sunken, until it begins to resemble a ravine. The point man begins to have a bad feeling about his route, because it resembles a place where he had conducted a successful ambush against an enemy patrol. With this on his mind, he spots two enemy soldiers lying in the tall weeds at the edge of the ravine to his left. The point man instantly recognizes that his squad has assaulted similarly sized forces across similar terrain with success in the past. He eminently opens fire, while shouting to his buddies, “Ambush left, 20 meters!” The rest of the squad, having been through this before, needs no elaborate explanation, but rushes through the enemy position with alacrity.

Again, our hypothetical patrol goes though the O.O.D.A. loop process, but, due to their past experience, they do so much more quickly. As Boyd found, he who OODA’s first, wins. Kline’s work found that the more experienced individuals make better decisions faster than less experienced people. That should come as a shock to no one. This brings us back to Private Cage from Edge of Tomorrow, and the question: how do we give someone experience without killing him in the process?

One answer is to simulate the experience. This immediately brings to mind million dollar flight simulators, and other training aids. As useful as these methods are, simulation is much older, and far simpler. Simulation can be as simple as two boxers sparing at 1/3 power, thus allowing them to learn the lessons of boxing without getting seriously hurt in the process. Long before any scientist studied these things, children were practicing war with games. Tag, hide- and- seek, and red rover are all war games. The nature and value of authentic simulation is a topic for another post, but with a force on force simulation, you really can do it all over again.

Training vs Simulation : Authenticity vs Realism

Ever had meaningful small unit tactics training with Nerf guns? I have.

Being highly involved in putting together the small unit training that One Shepherd provides and a war gamer, I’ve seen confusion and struggle when putting together something under either of these banners. Gamers often say they want realism in their war games when they usually mean authenticity, and vice-versa with trainers. Gamer’s ogle over realism when it’s not actually provided, and trainers strive too much for realism when then just need authenticity. Add in a factor of peoples desire for entertainment and it gets even more complicated.

Let me explain. First, we have to settle on terminology. We’ll define simulation and training, and then authenticity and realism.

In this context when I use the term simulation, it can basically be defined as a war game. According to Merriam-Webster, a war game is a simulated battle or campaign to test military concepts and usually conducted in conferences by officers acting as the opposing staffs : a two-sided umpired training maneuver with actual elements of the armed forces participating. This understanding automatically puts the focus on the testing and verification of military concepts. In other words, it’s just not built to being intentionally entertaining. It’s not really training either.

In the entertainment industry, there are more than a few games (board, video, or otherwise) that claim to do war gaming. Only a hand full actually do. I don’t begrudge them for that, because who wants to simulate walking land nav for three hours before hitting your objective of watching an empty valley all night – all while sitting at a computer screen. At the same time I say that, I can’t ignore game platforms like ARMA (which is the commercial version of Virtual Battle Space or VBS used by the US and forces around the world). It’s on its third iteration and has a worldwide following of over three million players. When employed under the banner of war gaming, ARMA/VBS becomes a valuable tool for anything from small unit tactics or as part of the Military Decision Making Process and everything in between. Here the Premack Principal applies though – very few people engage in a game marketed as entertaining for the specific purposes of training. They will endure training but only as long as that brings them a more entertaining experience.

Training on the other hand is defined as the act, process, or method of one that trains. People train to lift weights, type faster, and win at monopoly. It’s important to note that the objective of training is not necessarily reflected in the training itself. Training in push ups is useful for wrestling but it doesn’t show up in a match ever. What is important here is context provided by a good instructor. Training to shoot shapes and colors on a target as fast as possible on the instructors command doesn’t at all translate to a gunfight whatsoever. When re-framed in context of an exercise used to get the brain thinking about something other than the mechanics of shooting, that training becomes more tolerable.

The second set of terms that are often confused are authenticity and realism. These mean two very different things when it comes to training or war gaming. Authenticity is defined as conforming to an original so as to reproduce essential features. Realism, on the other hand, is concerned for fact or reality.

In both training and war gaming, the goal of training or war gaming must be clarified. This will help go a long way to align participants expectations. If you were a reenacting group, you would certainly align yourself with realism, usually down to the stitch. Authenticity has a different approach. Realism says, “That rucksack is the wrong color and doesn’t have the correct buckles!” Authenticity says, “He has a rucksack.”

This works both ways. Authenticity can take things too far as well. “My air-soft rifle holds ammunition” Sure it’s authentic in that it holds ammunition, but realism says, “A single magazine holes 300+ BB’s therefore you won’t need to reload during this CQB scenario and that isn’t realistic.” This is also true.

The best recent example of this was watching a master instructor teach mobile defense to a few squads. Rather than placing their practical exercise in the field with weapons and blanks, he chose to use Nerf guns on the FoB (Forward Operating Base). This constructive exercise was authentic with respect to the terminal learning objective. Due to the short range of the engagements along with a few other stipulated rules, the students were able to grasp all of the working parts of a mobile defense because they could see it. Without that condensed range, the students would have been left in small groups in the field without any situational awareness as to what other units were doing. They would have also wasted a lot of time with some groups not even engaging. They would only learn later through storied conversation as to what happened. By having an exercise that authentically positioned the students in a mobile defense within the confines of the game and associated rules, they were able to reach an real understanding of the lesson very quickly.

The relative assignment of training, simulation, authenticity, realism can be rather subjective. With that in mind, we’ll use the following graphic to summarize these points with a specific outcomes or objectives in mind.

Civil War Re-enacting, when taken completely seriously, is very realistic. It’s also very much a simulation in that they are testing (or in this case re-testing) specific military concepts. MDMP war gaming on the other had doesn’t necessarily care to have a completely realistic realm by which to test a concept. It might be entirely software based or quite often hashed out through dialogue among the battle staff in a room somewhere. ARMA based land nav is fun considering you can do it in an air conditioned room while eating a pizza. More fun than actually walking for hours on end through rough terrain. It’s authentic in that it can drive home the major points of land nav. It’s not very realistic in the sense that your pace count is always perfect regardless of slope or fatigue and you don’t have to worry about magnetic declination or interference. An F/A-18 Flight simulator is a 1:1 replica of all the working functions of its real counterpart and is therefore appropriate for most training oriented towards the operation of the aircraft controls and functions. It would not be appropriate for G-force training or how to fly inverted as these platforms are often motionless.

Whatever camp you are in, make sure you define your objectives clearly for all parties involved. This goes for instructors and participants. Training objectives should be clearly defined as an instructor and should be communicated somehow to the students. This can be done directly, or culturally through community expectations like the example found in kids sports teams that don’t keep score. Participants should also clarify their expectations and desires. Are you there to experience a realistic simulation or would you be better off framing your experience as authentic training for what you are wanting to accomplish? Be honest with yourself, but don’t be surprised when authentic training means you put down your rifle and pick up Nerf guns every once in a while.

Tactical Security Operations: The Screen

As I mentioned in my last article, ”Area and Local Security: Conceptual framing for Tactical Security Operations”, there are three similar, yet separate forms of TSO; Screen, Guard, and Cover. Each entail a progressively higher level of capability and requirements. These three categories employ a variety of tactics, techniques, and procedures to achieve success. They also entail a progressive level of active and passive resistance to enemy elements. These three forms fall under the category of tactical enabling, which, like its namesake suggests enables or shapes conditions for other types of operations.

The Screening Force Composition

The screening force is comprised of lightly numbered and armed elements, which are smaller elements of a larger force. The benefit to using the screen is the larger force can accomplish other tasks, while the smaller element provides early warning to the larger force. This enables the larger force time and space to react to enemy situations. The screening force seeks to find, monitor and or disrupt enemy reconnaissance activity. The larger friendly force uses a screening mission when; gaps exist between friendly forces, when friendly flanks, or rear are exposed and when the likelihood of enemy contact is remote and or the expected enemy force is small. Lastly the screening force may be used when the main friendly force only needs a minimum amount of time to react to a larger force.

The Screen Mission

A Screen is a mission requiring an element to provide early warning of enemy activity and or movement for a larger force. The Screen enables the larger friendly element to react upon discovery of enemy action. The Screen typically reports enemy activity and maintains visual/audio contact throughout the task. It may at times be tasked to disrupt enemy reconnaissance and infiltration activities through a variety of techniques. It should not, however be expected to disrupt forces more capable than reconnaissance elements due to its limited size and weapons capabilities. Screens can utilize several techniques to accomplish their task.

The Moving Screen

Roving patrols , or moving screens, help cover more ground and enable the screening force to actively seek out enemy reconnaissance elements. The Screen patrol can change its speed of march to force the enemy element to react.Changing the speed at which your screening patrol(s) move can catch your enemy off guard especially if its a larger size or you may force the enemy element to hide and evade your moving patrol. This patrols actively seek contact with the assumption that force will be used to disrupt enemy activity. Screening patrols must be prepared to make “Hard contact” or exchange fires. This does not preclude a moving screen from making “Soft contact” or visual only contact with the enemy once or for continued surveillance. Like any good game however, your opponent gets a vote and many have learned how to bypass moving screening patrols.

The Static Screen

The static or stationary screen, utilizes Listening Posts/Observation Posts (LP/OPs) to passively survey for enemy elements. This technique attempts in targeting enemy elements while they move and enables your elements to stay hidden, hopefully keeping the enemy elements unaware. The benefit to the Static Screen is that enemy elements may be looking for screening patrols but rarely find well placed LP/OP’s. LP/OP’s only require a minimum of two people, which can maximize the amount of friendly elements coverage area with a smaller force. The downsides to the static screen technique is that the enemy can quickly move out of visual contact with the LP/OP and will require another static or moving screen to regain contact, potentially risking a loss in contact with enemy forces. The traditionally smaller friendly LP/OP position is at risk from being overwhelmed by a larger enemy element.

The Combination Screen

The third technique is that of both Static LP/OP’s and Moving patrols. This combination of active and passive techniques seek to force the enemy to move away from roving patrols and into your static LP/OP’s contact. Once contact is made the moving patrols or a reserve can intercept enemy reconnaissance or infiltration elements while the LP/OP’s can remain hidden to continue their screening task. By having a variety of moving and static elements the enemy is forced to guess when and where you will have eyes and ears. The moving screen may stop and become static for extended periods to disrupt enemy action. These variations in moving and static positions must be coordinated prior too and communicated to all elements to ensure fratricide does not occur while friendly elements move about the battle space. When the larger parent element is moving, screening forces can continuously move to its front, rear and or flanks along side of the parent element, or remain temporarily static through halts. Additionally screening elements may choose to bound during the screen on the flanks through alternating or successive bounds.

What is the Size of a Screening Force?

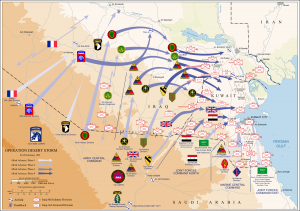

Historical examples of screens can show units as large as a division, much like the French 6th Light Armored Division during Opération Daguet which served as the Coalitions principal screening force for Operation Desert Shield in 1991, or as small as a fire team conducting a platoon/company sized operation in the jungles of Vietnam. Screening forces vary in size based on the larger unit that requires the screening. In addition a screening force is noted to have as few as possible numbers to accomplish the picking up and maintaining contact of the enemy (Economy of force). In the cases where a screen is tasked, having the smallest element possible gives the screening force added mobility to evade, and follow larger enemy elements, while picking up and harassing smaller enemy elements.

It should be noted that the screening force(s) will be as small as or smaller than and have less combat power than the estimated threat. Without this consideration the screening element could be tasked with something it cannot realistically accomplish and is doomed to defeat. If the force is larger than the anticipated threat then it could be reconsidered as an element capable of cover or guard and should be tasked as such with new commanders intent.

Where is the screen sent in relation to its larger friendly element?

The Screen is tasked and positioned based on the activity of the larger friendly element. The larger friendly element may be moving, or static itself. The larger unit has 360 degrees of potential enemy threat axis to worry about in non linear cases, or a more narrow front in linear cases and may task an element to screen to its front, flanks, or rear. In some linear cases the threat has specific axis’ and some areas may have a higher threat potential than others. The screening techniques will vary depending on the activity of the larger friendly unit and the situation at hand. The screening element needs to be far enough away from the parent element that it can provide accurate early warning, but stay close enough to be within the umbrella of its parent elements indirect fire support.

What if the enemy brings all of his friends?

The downside to a screen is that it only has small, lightly armed elements. If the enemy force is larger than friendly screening elements, the screen will not be able to disrupt the enemy force without risking its own life. It can augment size by conducting and initiating engagements at farther distances but any exposure to a larger element has an increased risk, turning a screening mission into a decisive engagement at worst or an evasion at best, which may result in a defacto loss of situational awareness, leaving your screening force useless. The Screening force has limited combat power, or potentially exhaustible resources to fight with. This may mean the best course of action (C.O.A.) is to report the situation, hide until the larger force moves past and either follow the larger enemy force at a safe distance, or continue screening in your assigned A.O. and letting the larger force go past once reported. Contingency plans should be made ahead of time with the larger unit outlining Rules of Engagement (R.O.E.) and actions to take if your screening element encounters a larger force.

What if we get into “hard” contact and fires are exchanged?

No other question is more relevant than this when firing starts. This is also the most difficult question to answer as each situation may dictate a different yet appropriate response. The critical deciding factor of action is as always the commanders intent and specifically the end state. What a Screen should not accomplish is the holding of ground or the blocking of enemy elements. This is reserved for the guard and or the cover respectively and because of your light and relatively weak task organization, you shouldn’t be expected to hold your ground. In the screen, if you find yourself engaged and the choice between holding ground or destroying the enemy requires you to lose your screening force, then RUN! You may even be able to slip away to get eyes on from another approach without firing back. Your larger element cant see or tell whats going on if your screening force is destroyed. The last caveat is a general rule for all engagements, if you become decisively engaged, meaning you cannot break contact either through your organic means or with help, then you must win the fight or die. Because of the balance between staying alive and reporting and harassing the enemy, units should practice this task often as part of their training cycle. This takes a heavy amount of small, local level leadership that usually occurs within a squad to fire team element on the small unit level and therefore requires low level leadership to not only understand how to screen, and the purpose, but also practice of exercising initiative while away from the main body in accord with the commanders intent.

The Raid: A Virtual Gaming Experience

Click READ ME below to see the video…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUtMpKt_i44

The Raid: Media Review

Click READ ME below to watch the video. There is nothing like a good crime movie to demonstrate the basic principals of the raid. The 1995 movie Heat with Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Val Kilmer is a pretty good example of that…

The After Action Review (AAR) – A Primer

After Action Reviews – or AAR’s. I see them a lot on blogs and forums. People post their “AAR” of whatever product or experience they came in contact with. You typically see AAR’s on a tactical hard or soft goods and even pistol or rifle courses. This is fairly appropriate as the AAR has it’s roots as a military practice. However, most of these writings are really product reviews labeled as an AAR in an attempt to appear “in the club”. These well meaning write ups often misrepresent the end goal of a real AAR.

Sometimes, in order to describe what something is, we have to identify what it’s not.

The AAR is a tool used by leadership to improve the effectiveness of the team they lead. As the name implies, this review process takes place after the particular action has already taken place. The AAR is actually a four step process. It really is worthy of a class all to itself so we won’t be discussing how to conduct one in this article. However, we can learn from it’s basic principles. The AAR is for the benefit of the team or teams involved. It is not necessarily for those outside of that group, though we can certainly learn from the experiences of others. In order to have meaningful participation in the AAR process, you have to understand the plan that was to be carried out.

You can’t do that if you don’t know what the plan was! If you weren’t there, you don’t actively participate.

Along that note, it’s very tempting to identify what you would have done differently and how it would have changed the outcome to a more positive one. It’s very tempting to play Armchair General. A word of caution to that – your opinion likely matters very little, since you weren’t privy to the particular Operations Order that preceded whatever event you are critiquing. Your review of a situation is always tricky if you weren’t there. Even if you were, be careful. I’ve been in firefights where the guy at the other end of the line 30m away had a completely different story to tell compared to what I did. Just look at the two different accounts of the raid against UBL and those guys were practically shoulder to shoulder.

It’s easy to say what you would have done, but you didn’t experience the same thing – that’s impossible. You can use it to stimulate thought and reflect internally on how you might bring about improvement.

Now, that doesn’t mean we can’t learn from the experiences of others. We most certainly can and that is encouraged. That is a different process though and is rather personal. You are most certainly entitled to your opinion on a particular event in history. However, the AAR is most decidedly not one’s opinion. One of critical tasks for an AAR facilitator is to steer emotion out of the discussion unless it was absolutely vital in the decision making process that followed.

The AAR is about redemption and positive reinforcement for the next time. It is not a medium by which to point fingers and place blame. Anyone who facilitates a real AAR will squash this type of behavior immediately.

Storytelling is a powerful way to convey an experience. The AAR should be a safe place to share your viewpoint on the operation. Be honest, be concise. Tell your story, but be sure to make it pertinent to the rest of the group. Telling the group how awesome your reload was isn’t helpful – unless you are confirming the effectiveness of training you received. Neither is telling the group how awfully they conducted a battle drill – unless you specifically rehearsed that before hand. There is a balance you must find.

With the right leadership, an AAR can be an effective tool for continuous improvement. In the wrong hands, it’s used to place blame. It can be used by anyone from little league coaches to corporate executives. What’s important is, regardless of what review tool you choose to use, be sure that it’s done for the betterment of the group – not to absolve the leader from the responsibility. If a leader isn’t there to be a servant those under his command, no review tool including the AAR can help.

Area and Local Security: Conceptual Framing for Tactical Security Operations for Small Units

This article was submitted to another site around 2014 and was never published.

Its almost spring again in Missouri and that means brushing off the cobwebs of winter and getting back in the field to teach leadership at One Shepherds’ Warrior Leader Program. (WLP) One of the students who is slotted for their primary leader position, which is required for their One Leader tab, approached me with a question concerning the screening patrol that he’ll be conducting during this Semesters Situational Training Exercise (STX). His question however prompted me to “unpack” my answer, which is heavy.

Historically, light infantry have always accomplished tactical enabling operations of their day. Although the modern concept and verbiage of “Light Infantry” has changed, tactical enabling operations are still required and conducted to set up the conditions for offensive and defensive success. Within the wide array of tactical enabling operations, security operations are foundational pillars of required concepts to understand and employ during operations.

The Roman Velites were some of the earliest forms of organized light infantry in a professional army. Chief among their duties was providing early warning of enemy activities and locations. This task provided friendly units with enough warning in time and distance (space) to react to the enemy, enabling friendly units to develop the situation with eyes and ears while main forces prepared and reacted to the changing stimulus. These units conducted security operations to the front, flanks, and rear of the larger force, moving forward of the main battle formation. This task illustrates “Local Security,” that is protecting the main body.

One of the means by which Velites would provide even more time and space was through the engagement of enemy elements with stand off weapons like the javelin, peppering battle lines of opposing troops and then withdrawing through their main friendly lines once their ordnance was thrown out or they encountered a heavier unit. By this limited means, Velites could draw combat power away from enemy elements, and force them to expend “combat power” or in other terms , firepower, manpower, maneuver, protection and information. By exhausting their opponents resources and energy the screening force could drain the enemy before the battle with main troops started.

Small in numbers and purposely augmented to have minimum equipment, these screening troops could utilize speed and mobility to their advantage. This however, meant that because of their relatively few numbers and little protection in both armor and in distance to robust line units, they were increasingly vulnerable to standard line infantry and cavalry units.

These Light Fighters were also tasked forward of the main body as vanguards as well as flank and rear security during administrative movements from bivouac to bivouac and during tactical approach marches and maneuvers. The concept of having security forces between their main body and the enemy enabled the Roman Army to develop the situation around them, provide early warning of enemy maneuver and enabled the disruption of attacks all while buying time and space for the larger main body to react and maneuver. While stationary in bivouac light units were tasked in guarding area water supplies away from camp, or main access roads that lead to the bivouac itself. This concept illustrates the focus of the area around the unit,which the unit intends or may need to utilize in order to further their objectives and not the unit itself, which developed the concept of “Area Security.”

Although Distances in between units during combat have changed due to technology, the need for Security Operations still exist. As mentioned above, one of the main categories of Enabling Operations is that of Security Operations.

There are two types of “Tactical Security Operations” (TSO) which are Area Security, and Local Security. BLUFOR doctrine stresses that all units provide their own local security from within the unit itself (organic) at each level down to the buddy team. Area Security, however is usually an assigned mission by a larger element to an adjacent or subordinate element. They are denoted in difference nominally by the distance to which the security element is operating from the main body and what its attempting to secure. Local security limits the distance a security element may be pushed out, focusing on protecting the unit itself. Some environmental aspect in which the unit deems “key” or decisive” may also be tasked to achieve the protection of the organic unit but the focus is still on preventing surprise actions by an enemy against the main unit. Local Security aims to protect the element itself, while Area Security encompasses features, both man made and natural, that influence the elements ability to conduct operations within its assigned area of operation. (A.O.) Area Security focuses on controlling or monitoring key terrain, which will give the force a marked advantage in operations, and or decisive terrain, which is terrain that will make or break the success of your operation.

In this example, the LP/OP’s serve as local security while the three moving patrols serve as area security.

The placement of these units is dictated by the principals of METT-TC and OCOKA.

Area security

- Pro: Elements have larger distances between them and the main body

- Enables earlier time for warning

- Enables more space for reaction and maneuver

- Protects valuable features other than but not limited from the main body

- Con: Elements have larger ground to cover

- Requires more people

- May require more specialized equipment

- Smaller recon and infiltration teams can penetrate through and around gaps between units

- Requires robust coordination between friendly elements who may be both static and moving

Local security

- Pro: Elements have a shorter distances between them and the main body

- Less gaps in the security enables spotting of smaller units

- Requires less people

- Lower strain on equipment and supplies (distance to communicate and to resupply is less)

- Eases coordination by shorting time and space.

- Economy of force is maximized due to distance

- Con: Elements have a shorter ground to cover

- Less early warning time

- Less space for reaction and maneuver

- Larger units may outrun or overwhelm local security forces

Both Area and Local concepts achieve their end state through three separate forms of TSO; screen, guard, cover, which all entail progressively higher levels of capability and requirements. These three categories employ a variety of tactics, techniques, and procedures to achieve success. Lastly what may look like Local Security to a large element may be an Area Security to the smaller element tasked. It should be noted that at all times within BLUFOR doctrine, every element no matter the size is required to establish and maintain continual local security. Security is a critical enabler in all operations and without it, effort and lives are lost.

Communications Breakdown: Part 1

The ability to communicate effectively is arguably the most important asset to any entity seeking to obtain a certain goal. Without communication the ability to relay ideas and goals to coworkers and teammates is nullified. Without properly conveying these ideas and goals to our team we fail to reach enabling and terminal objectives. It is not enough to simply open up a line of communication for the purposes of light fighting. A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) must be established in order to make communications seamless and proficient. Establishing a pattern or sequence for communication allows us to communicate successfully with other teammates. Standardizing communication is especially important because we may not even know those receiving our message very well. If communication was not standardized, efficiencies of time and message would be lost.

Communication is used in order to coordinate and assign tasks, as well as to maintain situational awareness of teams. In several circumstances we seek to keep our communications proprietary; couples do not openly discuss their finances, businesses try to keep their newest ideas secret from their competitors so that they may gain advantage in the marketplace. The idea of shielding one’s communication is evident in almost any situation in which communication is involved. In the military, this idea is condensed to Operational Security (OPSEC). In communications, OPSEC is maintained through the application of Cryptology; the study of codes.

In World War II, the Japanese could virtually decipher every code the United States was using to communicate, thus operational success suffered. The Japanese knew when, where, and what U.S. forces planned to do as a result of the compromised communications. It does not matter how big a hammer you have, if your opponent knows when and where you plan to use it, that hammer is rendered ineffective. The introduction of the Navajo Code Talkers by U.S. forces effectively secured communications against Japanese Intelligence.

The Navajo Code Talker’s Dictionary is an example of Signal Operating Instructions (SOI). An SOI decreases the time on the net (radio frequency) by shortening the length of messages and, more importantly, allowing the user to communicate in a secure manner on an otherwise insecure net. The complexity of an SOI varies depending on the mission and unit. For instance, the nature of one mission may require a large amount of time when radio communications are forbidden. In other words, the unit needs to maintain radio silence so as not to alert the opposing forces of friendly activity. Some prefer a short SOI with just a few brevity codes, while others prefer a more robust and comprehensive SOI. The contemporary age has afforded advances in cryptology that have made this form of communication all but obsolete. Encrypted radio signals no longer require militaries to code their messages when facing a less technologically advanced enemy. Regardless, there are several instances where this technology can fail or be rendered obsolete. Plus, not everyone has access to top-of-the-line communications equipment. Thus, the study and use of an SOI is still quite valuable; especially in a leadership capacity.

One of the most noticeable traits of good leaders is their ability to communicate effectively. This entails the ability to express their vision through Commander’s Intent (CI) as well as disseminate information under stress. In One Shepherd’s Technical Institute of Leadership, we apply the use of SOI during training to not only shield communications from the Opposing Force (OPFOR), but also to facilitate our student leaders in learning how to communicate effectively under stress. Using an SOI in stressful situations forces the user to condense the message down to its simplest form. Thus, teaching leaders the art of clear and concise communication. In order for leaders to apply the use of SOI, they must first learn its composition and how to employ it.

So what goes into an SOI? Due to the comprehensive nature of this topic, this article will condense the information into five main points; Call Signs, SOI Timeline, Encryption Code/ Authentication Table, Passwords, and Brevity Codes. An example of SOI will help gain a more comprehensive understanding of its use.

Example format of the “required” information in an SOI.

Not every member of the patrol carries a radio, but every member must be familiar with the SOI should they be the one to need to communicate using the radio. Part 1 of this article will focus on the portions that every member of the patrol must be familiar with as they are explicitly non-radio based – the SOI Timeline and Passwords.

SOI Timeline:

This section is rather intuitive. By extensive use of the same SOI, the opposition is allotted the time and repetitiveness to decipher our SOI. Thus, an SOI is only used for a designated time; often 24 hours. In the above timeline, you should observe that the SOI is in effect starting at 071630SNOV14. This is a Date Time Group (DTG) of the form DDHHMMT MM YY. So the first part “07” represents the 7th day. The next four numbers represent the time “1630” or 4:30 P.M. Next we have “S” which is the Time Zone designator for Central Time. “NOV” represents the month of November and finally “14” indicates the year 2014. So putting everything together we get that the date time group is saying that the SOI will go in effect at 16:30 Central time on the 7th of November, 2014.

Passwords:

When linking up with another unit, each other, or simply making contact with another person in the field, it is imperative to immediately identify whether they are “friend or foe”. We do this through Challenge and Passwords. An all too familiar Challenge and Password is that of the Allied forces during WWII – Thunder and Flash. The movie Saving Private Ryan contains several classic examples of passage of lines. Passage of lines is conducted several times with the Challenge and Password to confirm the identity of each other. This film contains a fatal flaw. When giving a challenge and password it would be extremely easy to pick-up the challenge of ‘thunder’ and the password of ‘flash’. The proper (more secure) way of conducting the challenge and password would be to incorporate the two words into a sentence. Using the example table from above, it may look something like this:

Challenge

“Halt! Did you find the Badger in the garden?”

Password

“Nah, but we did locate a Priest so that Joe can go to confession”

The incorporation of the Challenge and Password into a sentences make it less obvious to a spy/ scout/ or enemy nearby. Another important step to this process is to inform the challenger of how many people you have with you so they may count them in. This is a procedure used to maintain a unit head count as well as keep an enemy spy from infiltrating your patrol; however unlikely it may be. Sometimes we know that we are going to make contact with another unit and we do not have the time and luxury of stopping and having this dialogue. In situations like this, we use what we call a running password. When using a running password you continuously yell out the word AND the number of people you have with you. A fellow warrior you are running towards hears you call out the running password, he knows you are friendly and that you are in a hurry. Secondly, he hears you call out a number and he knows how many friendlies are following you. For instance, you hear “Popcorn 5, Popcorn 5…” You know that 5 friendlies are coming in. Any one after that is considered an enemy.

“One, Two, Three, Four, and Five……… wait Six? (BANG!!!)”

The other password you see in the table is the number combination. With the number combination, the sum of the challenge and password must equal the designated number. Above we have the number combination of “Five”. The challenge can be anything less than five and the password has to be the number that creates the sum of five (i.e. – Challenge “2”, so Password is “3”; 2+3 = 5). While not necessarily required, you should incorporate these numbers into a sentence similar to the Challenge and Password from before. Using the same number combination, 5, it may look something like this:

Challenge

“Halt! Did you get those 4 apples I asked for?

Password

“Yes, and I found 1 raccoon too!”

Here we can see that 4 and 1 add to make 5, thus completing the number combination. While you can standardize when, or even if, you use each type of password, the general rule of thumb is that number combinations are used behind enemy lines and the Challenge and Password is used behind friendly lines.

Conclusion: Part 1

Every member of the patrol should be familiar with the Timeline and Password portions of the SOI. These basic building blocks should be rehearsed prior to step off and the patrol leader should quiz the members of the patrol on these two areas during the pre-combat inspection (PCI). Without these communication control measures in place, the entire operation can be compromised should an enemy sneak into your patrol. Even worse is avoidable fratricide. Learn and practice these basic concepts first, and you’ll be well on your way to maintaining solid communications with your team.