Counterattack, Pursuit & Exploitation – MTC

Meeting Engagement – MTC

The Most Common Attack! – MTC

Tactical Security Operations: The Screen

As I mentioned in my last article, ”Area and Local Security: Conceptual framing for Tactical Security Operations”, there are three similar, yet separate forms of TSO; Screen, Guard, and Cover. Each entail a progressively higher level of capability and requirements. These three categories employ a variety of tactics, techniques, and procedures to achieve success. They also entail a progressive level of active and passive resistance to enemy elements. These three forms fall under the category of tactical enabling, which, like its namesake suggests enables or shapes conditions for other types of operations.

The Screening Force Composition

The screening force is comprised of lightly numbered and armed elements, which are smaller elements of a larger force. The benefit to using the screen is the larger force can accomplish other tasks, while the smaller element provides early warning to the larger force. This enables the larger force time and space to react to enemy situations. The screening force seeks to find, monitor and or disrupt enemy reconnaissance activity. The larger friendly force uses a screening mission when; gaps exist between friendly forces, when friendly flanks, or rear are exposed and when the likelihood of enemy contact is remote and or the expected enemy force is small. Lastly the screening force may be used when the main friendly force only needs a minimum amount of time to react to a larger force.

The Screen Mission

A Screen is a mission requiring an element to provide early warning of enemy activity and or movement for a larger force. The Screen enables the larger friendly element to react upon discovery of enemy action. The Screen typically reports enemy activity and maintains visual/audio contact throughout the task. It may at times be tasked to disrupt enemy reconnaissance and infiltration activities through a variety of techniques. It should not, however be expected to disrupt forces more capable than reconnaissance elements due to its limited size and weapons capabilities. Screens can utilize several techniques to accomplish their task.

The Moving Screen

Roving patrols , or moving screens, help cover more ground and enable the screening force to actively seek out enemy reconnaissance elements. The Screen patrol can change its speed of march to force the enemy element to react.Changing the speed at which your screening patrol(s) move can catch your enemy off guard especially if its a larger size or you may force the enemy element to hide and evade your moving patrol. This patrols actively seek contact with the assumption that force will be used to disrupt enemy activity. Screening patrols must be prepared to make “Hard contact” or exchange fires. This does not preclude a moving screen from making “Soft contact” or visual only contact with the enemy once or for continued surveillance. Like any good game however, your opponent gets a vote and many have learned how to bypass moving screening patrols.

The Static Screen

The static or stationary screen, utilizes Listening Posts/Observation Posts (LP/OPs) to passively survey for enemy elements. This technique attempts in targeting enemy elements while they move and enables your elements to stay hidden, hopefully keeping the enemy elements unaware. The benefit to the Static Screen is that enemy elements may be looking for screening patrols but rarely find well placed LP/OP’s. LP/OP’s only require a minimum of two people, which can maximize the amount of friendly elements coverage area with a smaller force. The downsides to the static screen technique is that the enemy can quickly move out of visual contact with the LP/OP and will require another static or moving screen to regain contact, potentially risking a loss in contact with enemy forces. The traditionally smaller friendly LP/OP position is at risk from being overwhelmed by a larger enemy element.

The Combination Screen

The third technique is that of both Static LP/OP’s and Moving patrols. This combination of active and passive techniques seek to force the enemy to move away from roving patrols and into your static LP/OP’s contact. Once contact is made the moving patrols or a reserve can intercept enemy reconnaissance or infiltration elements while the LP/OP’s can remain hidden to continue their screening task. By having a variety of moving and static elements the enemy is forced to guess when and where you will have eyes and ears. The moving screen may stop and become static for extended periods to disrupt enemy action. These variations in moving and static positions must be coordinated prior too and communicated to all elements to ensure fratricide does not occur while friendly elements move about the battle space. When the larger parent element is moving, screening forces can continuously move to its front, rear and or flanks along side of the parent element, or remain temporarily static through halts. Additionally screening elements may choose to bound during the screen on the flanks through alternating or successive bounds.

What is the Size of a Screening Force?

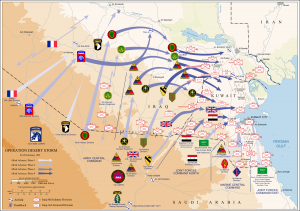

Historical examples of screens can show units as large as a division, much like the French 6th Light Armored Division during Opération Daguet which served as the Coalitions principal screening force for Operation Desert Shield in 1991, or as small as a fire team conducting a platoon/company sized operation in the jungles of Vietnam. Screening forces vary in size based on the larger unit that requires the screening. In addition a screening force is noted to have as few as possible numbers to accomplish the picking up and maintaining contact of the enemy (Economy of force). In the cases where a screen is tasked, having the smallest element possible gives the screening force added mobility to evade, and follow larger enemy elements, while picking up and harassing smaller enemy elements.

It should be noted that the screening force(s) will be as small as or smaller than and have less combat power than the estimated threat. Without this consideration the screening element could be tasked with something it cannot realistically accomplish and is doomed to defeat. If the force is larger than the anticipated threat then it could be reconsidered as an element capable of cover or guard and should be tasked as such with new commanders intent.

Where is the screen sent in relation to its larger friendly element?

The Screen is tasked and positioned based on the activity of the larger friendly element. The larger friendly element may be moving, or static itself. The larger unit has 360 degrees of potential enemy threat axis to worry about in non linear cases, or a more narrow front in linear cases and may task an element to screen to its front, flanks, or rear. In some linear cases the threat has specific axis’ and some areas may have a higher threat potential than others. The screening techniques will vary depending on the activity of the larger friendly unit and the situation at hand. The screening element needs to be far enough away from the parent element that it can provide accurate early warning, but stay close enough to be within the umbrella of its parent elements indirect fire support.

What if the enemy brings all of his friends?

The downside to a screen is that it only has small, lightly armed elements. If the enemy force is larger than friendly screening elements, the screen will not be able to disrupt the enemy force without risking its own life. It can augment size by conducting and initiating engagements at farther distances but any exposure to a larger element has an increased risk, turning a screening mission into a decisive engagement at worst or an evasion at best, which may result in a defacto loss of situational awareness, leaving your screening force useless. The Screening force has limited combat power, or potentially exhaustible resources to fight with. This may mean the best course of action (C.O.A.) is to report the situation, hide until the larger force moves past and either follow the larger enemy force at a safe distance, or continue screening in your assigned A.O. and letting the larger force go past once reported. Contingency plans should be made ahead of time with the larger unit outlining Rules of Engagement (R.O.E.) and actions to take if your screening element encounters a larger force.

What if we get into “hard” contact and fires are exchanged?

No other question is more relevant than this when firing starts. This is also the most difficult question to answer as each situation may dictate a different yet appropriate response. The critical deciding factor of action is as always the commanders intent and specifically the end state. What a Screen should not accomplish is the holding of ground or the blocking of enemy elements. This is reserved for the guard and or the cover respectively and because of your light and relatively weak task organization, you shouldn’t be expected to hold your ground. In the screen, if you find yourself engaged and the choice between holding ground or destroying the enemy requires you to lose your screening force, then RUN! You may even be able to slip away to get eyes on from another approach without firing back. Your larger element cant see or tell whats going on if your screening force is destroyed. The last caveat is a general rule for all engagements, if you become decisively engaged, meaning you cannot break contact either through your organic means or with help, then you must win the fight or die. Because of the balance between staying alive and reporting and harassing the enemy, units should practice this task often as part of their training cycle. This takes a heavy amount of small, local level leadership that usually occurs within a squad to fire team element on the small unit level and therefore requires low level leadership to not only understand how to screen, and the purpose, but also practice of exercising initiative while away from the main body in accord with the commanders intent.

The Raid: A Virtual Gaming Experience

Click READ ME below to see the video…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUtMpKt_i44

The Raid: Media Review

Click READ ME below to watch the video. There is nothing like a good crime movie to demonstrate the basic principals of the raid. The 1995 movie Heat with Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino, and Val Kilmer is a pretty good example of that…

Area and Local Security: Conceptual Framing for Tactical Security Operations for Small Units

This article was submitted to another site around 2014 and was never published.

Its almost spring again in Missouri and that means brushing off the cobwebs of winter and getting back in the field to teach leadership at One Shepherds’ Warrior Leader Program. (WLP) One of the students who is slotted for their primary leader position, which is required for their One Leader tab, approached me with a question concerning the screening patrol that he’ll be conducting during this Semesters Situational Training Exercise (STX). His question however prompted me to “unpack” my answer, which is heavy.

Historically, light infantry have always accomplished tactical enabling operations of their day. Although the modern concept and verbiage of “Light Infantry” has changed, tactical enabling operations are still required and conducted to set up the conditions for offensive and defensive success. Within the wide array of tactical enabling operations, security operations are foundational pillars of required concepts to understand and employ during operations.

The Roman Velites were some of the earliest forms of organized light infantry in a professional army. Chief among their duties was providing early warning of enemy activities and locations. This task provided friendly units with enough warning in time and distance (space) to react to the enemy, enabling friendly units to develop the situation with eyes and ears while main forces prepared and reacted to the changing stimulus. These units conducted security operations to the front, flanks, and rear of the larger force, moving forward of the main battle formation. This task illustrates “Local Security,” that is protecting the main body.

One of the means by which Velites would provide even more time and space was through the engagement of enemy elements with stand off weapons like the javelin, peppering battle lines of opposing troops and then withdrawing through their main friendly lines once their ordnance was thrown out or they encountered a heavier unit. By this limited means, Velites could draw combat power away from enemy elements, and force them to expend “combat power” or in other terms , firepower, manpower, maneuver, protection and information. By exhausting their opponents resources and energy the screening force could drain the enemy before the battle with main troops started.

Small in numbers and purposely augmented to have minimum equipment, these screening troops could utilize speed and mobility to their advantage. This however, meant that because of their relatively few numbers and little protection in both armor and in distance to robust line units, they were increasingly vulnerable to standard line infantry and cavalry units.

These Light Fighters were also tasked forward of the main body as vanguards as well as flank and rear security during administrative movements from bivouac to bivouac and during tactical approach marches and maneuvers. The concept of having security forces between their main body and the enemy enabled the Roman Army to develop the situation around them, provide early warning of enemy maneuver and enabled the disruption of attacks all while buying time and space for the larger main body to react and maneuver. While stationary in bivouac light units were tasked in guarding area water supplies away from camp, or main access roads that lead to the bivouac itself. This concept illustrates the focus of the area around the unit,which the unit intends or may need to utilize in order to further their objectives and not the unit itself, which developed the concept of “Area Security.”

Although Distances in between units during combat have changed due to technology, the need for Security Operations still exist. As mentioned above, one of the main categories of Enabling Operations is that of Security Operations.

There are two types of “Tactical Security Operations” (TSO) which are Area Security, and Local Security. BLUFOR doctrine stresses that all units provide their own local security from within the unit itself (organic) at each level down to the buddy team. Area Security, however is usually an assigned mission by a larger element to an adjacent or subordinate element. They are denoted in difference nominally by the distance to which the security element is operating from the main body and what its attempting to secure. Local security limits the distance a security element may be pushed out, focusing on protecting the unit itself. Some environmental aspect in which the unit deems “key” or decisive” may also be tasked to achieve the protection of the organic unit but the focus is still on preventing surprise actions by an enemy against the main unit. Local Security aims to protect the element itself, while Area Security encompasses features, both man made and natural, that influence the elements ability to conduct operations within its assigned area of operation. (A.O.) Area Security focuses on controlling or monitoring key terrain, which will give the force a marked advantage in operations, and or decisive terrain, which is terrain that will make or break the success of your operation.

In this example, the LP/OP’s serve as local security while the three moving patrols serve as area security.

The placement of these units is dictated by the principals of METT-TC and OCOKA.

Area security

- Pro: Elements have larger distances between them and the main body

- Enables earlier time for warning

- Enables more space for reaction and maneuver

- Protects valuable features other than but not limited from the main body

- Con: Elements have larger ground to cover

- Requires more people

- May require more specialized equipment

- Smaller recon and infiltration teams can penetrate through and around gaps between units

- Requires robust coordination between friendly elements who may be both static and moving

Local security

- Pro: Elements have a shorter distances between them and the main body

- Less gaps in the security enables spotting of smaller units

- Requires less people

- Lower strain on equipment and supplies (distance to communicate and to resupply is less)

- Eases coordination by shorting time and space.

- Economy of force is maximized due to distance

- Con: Elements have a shorter ground to cover

- Less early warning time

- Less space for reaction and maneuver

- Larger units may outrun or overwhelm local security forces

Both Area and Local concepts achieve their end state through three separate forms of TSO; screen, guard, cover, which all entail progressively higher levels of capability and requirements. These three categories employ a variety of tactics, techniques, and procedures to achieve success. Lastly what may look like Local Security to a large element may be an Area Security to the smaller element tasked. It should be noted that at all times within BLUFOR doctrine, every element no matter the size is required to establish and maintain continual local security. Security is a critical enabler in all operations and without it, effort and lives are lost.

Worst Case Scenario: Behind Enemy Lines

“We’re paratroopers, Lieutenant. We’re supposed to be surrounded.” – CPT Richard “Dick” Winters at the Battle of the Bulge

It’s an oddity of battle that there are numerous tactical reasons to find oneself behind enemy lines. An envelopment or in the case of airborne troops a vertical envelopment will almost invariably and intentionally place friendly forces behind enemy lines to achieve specific effects.

Of course, this is not what we mean when we say “caught behind enemy lines.” This expression refers to those cases when our troops unintentionally find themselves behind enemy lines – be it the result of a delaying force conducting retrograde that was cut off from their retreat; or an attacking force that simply pressed too far ahead for the overextended main body, reserves and logistics to keep pace.

Thus, while CPT Winters’ comments at the Battle of the Bulge are admirably stoic and even border on heroic, the situational assessment of the young armor officer, to whom CPT Winter’s was speaking, was probably more accurate. The US paratroopers had not been dropped into Bastogne. They walked. And the German Army was rapidly enveloping them.

Whatever the cause, being isolated behind enemy lines is a perplexing situation as well as a considerably dangerous place to be! Behind enemy lines friendly logistics are hard pressed to re-supply your force on ammunition, water, batteries, medical supply or evacuation, or even achieve something so mundane as to feed your troops. Things could get desperate, quickly.

Furthermore, the enemy is bound to outnumber you, and if they haven’t discovered your force yet, they likely soon will. Time isn’t on your side.

If this doesn’t sound bad enough, realize that linking up with friendly forces isn’t as simple as just surreptitiously maneuvering across the battlefield to some imaginary line on a map. Oh no, some friendly unit somewhere close by just took a mauling. Think about it. If that wasn’t the case, your unit probably wouldn’t be stuck behind enemy lines right now.

So merely waltzing up to the good guys and saying, “Hey it’s us. Red rover, red rover, let us come on over” isn’t going to cut it in middle of a violent melee or its immediate aftermath. That’s a good way to get killed by friendly fire. The troops are nervous and probably ready to shoot the first target they encounter. You have to approach with a healthy amount of careful coordination.

But the news may not be all bad. You’ll have to take a quick assessment of your situation and look for opportunities to emerge.

Timing and Proximity

Frankly, if you’ve just been cut off in the last half hour or so, and are in close proximity to your line, listen to the battlefield. You are likely not out of ammunition yet. You have an opportunity to strike the enemy from a direction for which they are simply ill prepared. And the defeat of an enemy force may very well create an opportunity for you to link up with friendly forces.

Be careful here. Remember that the friendly line will be shooting direct fires and indirect fires back at the attacking enemy force. If you get in too close to their formations, you’ve become a target for friendly fire – and they almost certainly don’t realized that your small force is mixed in with the enemy. You could wind up on the receiving end of both friendly and enemy fires simultaneously.

On the other hand, if you play it too far back you won’t be able to significantly contribute to the fight. The idea is to position your team so that you can place punishing fires on the enemy at key points in their assault – against the rear of their support section, or on the flank of their breach team. A hard hit against one of these teams might very well sway the balance of the fight.

On the other hand, if you play it too far back you won’t be able to significantly contribute to the fight. The idea is to position your team so that you can place punishing fires on the enemy at key points in their assault – against the rear of their support section, or on the flank of their breach team. A hard hit against one of these teams might very well sway the balance of the fight.

When the enemy is repelled and falls back off the objective, you must make your team’s presence known at the first available lull in the firing. Again, expose yourself too quickly and you’ll be mistaken for an enemy force. Wait too late and both forces may have maneuvered so drastically that you’ve become lost again.

It is critical that you do not attempt to reenter the friendly lines during an enemy attack on the friendly unit! Again, that’s just too much coordination for the unit under attack to bear. It will end disastrously, regardless of the best intentions.

Daylight vs. Nighttime

If you are not in the immediate vicinity of friendly forces, the opportunity to slip back into friendly lines may be more difficult. In fact, you may already be surrounded by enemy forces. This situation dictates that you almost certainly have to slip away during periods of darkness.

Communication is critical. You’ll have to contact the nearest friendly force and coordinate a far recognition signal and a near recognition signal. Furthermore, you’ll have to establish a time and place for your team to approach the friendly line. Under periods of darkness, this can be daunting.

Truth be told, the same information is required to reenter the friendly line during daylight hours, but since visibility is an advantage in daylight, the coordination is much easier. And the friendly troops are a bit less nervous.

If you can pull it off at all, reenter the friendly line during daylight hours.

Using either speed or stealth, or a combination of the two, maneuver to the determined location of the friendly line. Immediately offer the far recognition signal in the manner prescribed – i.e. pop a color smoke, waive a color panel, or flash a color light lens – and wait for the friendly force to authenticate the color. Once they’ve done that, send a small link up team to render the near recognition signal as prescribed. This is usually a numbered challenge and password.

Once the link up has been achieved, a security team needs to collect or wave in the remainder of your team. Each member is counted in by name to demonstrate that everyone is recognized on the lost patrol.

Going in Blind

But what if you have no communications with the friendly forward line (FFL)? What if you must evade the enemy while crossing a large engagement area – “no man’s land”? And what if local friendly forces are unaware that your unit is cut off?

Okay, this is the worst of the worst case scenario. It’s definitely not a desirable situation to be in, and so I’m going to suggest the only solution I can think of. Surrender.

Okay, this is the worst of the worst case scenario. It’s definitely not a desirable situation to be in, and so I’m going to suggest the only solution I can think of. Surrender.

No, not to the enemy! Surrender to your own friendly forces. You may need to cache your weapons and equipment nearby for later retrieval. Select the most inconspicuous path toward the FFL and move carefully toward friendly forces. Once you’re team is within sight, select a small team to stand up and wave the white flag of surrender – white under pants, a t-shirt, several pairs of white tube socks. Oh heck, it doesn’t even have to be white.

The important thing is to wave something during hours of excellent visibility so that the friendly forces can see that you are unarmed and attempting to surrender. Once they understand this, the battle is half over for you.

Yet remember that if your team is exposed in a particularly large engagement area, you are also vulnerable to enemy fires. You need to get your team out of the engagement area as quickly as possible, while making it clear to the friendly forces that you are surrendering.

Again, linking up with the FFL from the enemy side of the engagement area is daunting at best, and should be done during daylight hours if at all possible. Careful communication and coordination must be implemented. In lieu of this solid advice, simply surrender to the good guys.

Hey, humiliating as it is, it’s much better than the alternative – surrendering to the bad guys!

This article was originally published on odjournal.com (Olive Drab: the journal of tactics) and has been transferred here with permission.

Elusiveness: Force protection means being hard-to-kill

As with any other aspect of warfare, force protection includes various measures and concerns, with situational awareness, simply knowing what’s coming next, being preeminent. Too, it’s always a good idea to establish 360 degree security around us; an umbrella of protected space above us; and a networked bubble below us. For large formations of troops, say a brigade, division or coalition joint task force there is little in the way of alternative options

For small tactical units there is another option in force protection, elusiveness. The state of being hard-to-kill means being so elusive that you become a hard target to, well…target.

Elusiveness is achieved through either mobility or stealth. One or the other, at least in terms of land forces. True, aircraft achieve an element of both, though primarily they use mobility. Fast moving aircraft are difficult to shoot down even when we are completely aware of their presence. Still, aircraft do employ stealth technology from electronic detection, and can always fly into cloud cover (when available) to avoid visual tracking. The reverse is true for submarines. These vessels use underwater stealth as their primary form of elusiveness, though indeed submarines can achieve fairly impressive speeds, at least in terms of watercraft.

Elusiveness is achieved through either mobility or stealth. One or the other, at least in terms of land forces. True, aircraft achieve an element of both, though primarily they use mobility. Fast moving aircraft are difficult to shoot down even when we are completely aware of their presence. Still, aircraft do employ stealth technology from electronic detection, and can always fly into cloud cover (when available) to avoid visual tracking. The reverse is true for submarines. These vessels use underwater stealth as their primary form of elusiveness, though indeed submarines can achieve fairly impressive speeds, at least in terms of watercraft.

Land-borne forces do not enjoy such a blurring of the line. Vehicles move humans quickly across the terrain. But vehicles are also large and loud, easily seen and easily heard. This is reasonably true even for the smallest land vehicles such as motorcycles, and also true for large armored vehicles such as the Stryker. And lest we fall into the trap of thinking some semblance of stealth can be achieved with airborne vehicles – nope. Blackhawk helicopters and Osprey hybrid fixed wing vehicles are easily seen and heard, too.

I’ve spent a respectable number of years in both air assault and mechanized infantry regiments. In all those years I’ve never had a vehicle “sneak up” on me.

Yet the noise and visibility of combat vehicles shouldn’t be interpreted as malfunction or deficiency. Regardless of the ease of detection, combat vehicles offer fantastic advantage to their passengers and crew. There is some protection from projectiles zipping about the battlefield, even in relatively thin-skinned vehicles. The weaponry and munitions that vehicles carry when compared to dismounted troops is nothing less than awesome. And perhaps most importantly of all is that such vehicles offer mobility.

It’s not merely the difficulty in targeting and scoring a hit against a moving vehicle, yes that’s difficult enough. But it’s also that mobility, more specifically speed, allows these forces to quickly move out of gunnery range or at least rapidly find suitable cover. This attribute alone can render powerful, sophisticated weaponry ineffective, or even obsolete.

Even when excellent gunnery is capable of scoring hits against highly mobile forces, the impact is usually minimal. Yes, a vehicle is almost certainly lost, but the passengers and crew are quickly swept up by another vehicle and the mobile force continues on its way.

Think of the cavalry during the American Civil War. Even when the foot soldier managed to down a horse, the horseman almost invariably jumped onto the back of another cavalrymen’s horse and away they went. This had to be incredibly frustrating to the infantrymen who had to withstand the pulsing attacks of highly mobile mounted troops.

The same dynamic exists today. Watch the videos of the Taliban cheering while standing on a burnt-out hull of a Coalition Forces vehicle. How often to you see the bodies of Coalition Forces in those videos? Almost never. Yet you can bet if the Taliban could show off the bodies of their dead enemies, they most certainly would! So instead the Taliban are left with little option but to make a “big show” of a burnt vehicle, while they lose more and more of their warriors to highly mobile Coalition Forces every day. That has to be frustrating for the enemy.

Mobility is a form of elusiveness.

Stealth, then, is the other form of elusiveness. And when we think of elusiveness, we tend to immediately think in terms of stealth. Heavily vegetated forests and jungles, or forbiddingly steep mountains are ideal terrain to achieve stealth.

The physical dynamics of flat, open terrain lend well to mobile forces while playing a distinct disadvantage to forces employing stealth. It’s not necessarily the case that a small tactical element couldn’t be stealthy in their approach across a desert plain. But it is much more difficult to achieve success in this effort, and if the stealthy dismounted force were detected in open terrain by a mobile force, their doomed fate is sealed.

The physical dynamics of flat, open terrain lend well to mobile forces while playing a distinct disadvantage to forces employing stealth. It’s not necessarily the case that a small tactical element couldn’t be stealthy in their approach across a desert plain. But it is much more difficult to achieve success in this effort, and if the stealthy dismounted force were detected in open terrain by a mobile force, their doomed fate is sealed.

Modern technology hinders stealth in such terrain all the more. Passive light night vision devices and the impressive Forward Looking Infra-Red (FLIR) detect the human form with great reliability.

Again, this is not to overstate the crutch of technology. When employing stealth, the clever use of a defilade waddi or ravine can be used to avoid detection. Furthermore even FLIR has its limitations. In the hottest part of the day the desert floor becomes so heated that a human body is able to “hide” in the FLIR image. It’s like hiding a needle in a needle stack. And in the snow covered tundra, ample use of snow banks and drifts can achieve a similar effect in hiding the elusive force from the peering eye of FLIR and passive light detection.

Still, the use of stealth is better suited to vastly vegetated terrain where a stealthy patrol isn’t canalized into natural chokepoints to become easy prey for passive light and FLIR detection.

Stealth is slow. Speed is not the objective, nor can speed be counted on as a form of security during stealthy patrolling operations. Stealth relies instead on camouflage from enemy detection, and maintaining an upper hand in situational awareness.

We need to know where the enemy is, and isn’t, while keeping the enemy confused as to our location. This is critical. If the enemy detects us they will bring their firepower to bear, of course. That might mean the enemy employs highly mobile troops using direct fires, and yes, Close Air Support (CAS) is included in this. It might also mean indirect fires of the enemy’s long range mortar and artillery. In any case, detection can be fatal to a stealthy, slow, dismounted patrol.

In Vietnam during the late 1960s, US battalions of the 187th Rakkasan Airborne (ABN) regiment and the 199th Light Infantry Brigade (LIB) were tasked to interdiction operations against infiltrating elements of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). Regiments of NVA Regulars were using the Ho Chi Minh Trail to gain access to the porous mountain border of Vietnam and Cambodia, and into the triple canopy jungles of the central highlands.

The 187th Rakkasans and 199th LIB took two very different approaches to the problem, though arguably both were equally effective.

Knowing the enemy employed artillery and mortar fires from entrenched safe havens unevenly dispersed throughout the central highlands, both the 187th and 199th dispatched rifle companies to conduct ambushes and deliberate attacks against enemy formations. Common to that conflict, rifle companies were often undersized at just 90 to 100 troops instead of the allotted 140.

The 187th Rakkasans chose to use a stealthy approach. They would enter the jungle valleys from firebases or by means of helicopter insertions, making use of ample false insertions to confuse the NVA as to the actual location of the rifle company. Once in, the Rakkasans would ever so slowly snake their way through the valleys and mountain ridgelines to an intended target. The patrol would take days, sometimes a week or more.

Progress was painfully slow. The pointman as well as every troop in the linear formation had to make a hundred decisions and assumptions every day. Do you move to the sound of the water? The troops need to top off canteens, but water brings unwanted enemy traffic. Do you move to the sound or smell of enemy encampments? If this is not the rifle company’s intended target, an early engagement would disclose the rifle company’s position and put it in a fight before it could get to its target. Yet, tracking and shadowing a small enemy patrol might also lead the rifle company directly to its intended target.

Each Soldier stepped carefully, deliberately. The enemy laid mechanical ambushes just as we did. Booby traps lined the foot paths. It was best to avoid those.

Each Soldier moved vegetation carefully around them. To snap branches or clumsily shove at vines would make unnecessary noise and invite the attention of enemy patrols. If discovered, the Rakkasans could expect a hailstorm of indirect fires from entrenched enemy artillery and mortars – or worse, an assault wave of the nearest NVA battalion.

Each Soldier carried what they’d need for three to five days at a time, food, water, ammunition, batteries, and medical supplies. Equipment had to be secured, tied and taped. Radios had to be muffled with socks and plastic wrap. Hard surfaces softened so as not to make so much noise. Camouflage grease was applied to skin and shiny metal objects. Often even the baggy portions of trousers and blouses were wrapped tight with friction tape.

It was heavy going in such hot, humid conditions. A 100-troop rifle company would stretch for 300 meters through the mountain jungles. Though most days a rifle company would travel on average one to two kilometers, some days they only moved 100 meters. This meant the Soldiers in the back of the column pulled guard that night in the very same positions the Soldiers at the front of the column had used the night before.

Within a week’s time, the Rakkasans would have moved perhaps five kilometers. They then sprung an attack on a very unsuspecting enemy. The rifle company could call for fires from its own artillery emplacements, and if the target was marked clearly enough the rifle company might even risk CAS in the triple canopy jungle.

The attack or ambush was almost always quick and clean. Few of the enemy survived to offer much information to sister NVA battalions. And typically by that time the Rakkasans had slipped away into the jungle, stealthy and elusive.

The 199th Light, by comparison, would have nothing to do with that sort of fighting! Even though the 199th was also on foot, they chose an altogether bolder approach to engaging the NVA. They would march.

Each morning prior to the patrol the 199th rifle companies would palletize their gear. And not just the mortars and recoilless rifles. No, they’d palletize their rucksacks, body armor, plus extra water, C-Rations and ammunition to be flown out each morning, sling-loaded by helicopter. When a light rifle company started to march, the troops carried a single meal for the day and water. Beyond that it was just radios, weapons and ammunition.

The light rifle company could easily cover a dozen kilometers in a single day, provided they didn’t come in contact with a sizable enemy force. The 199th Light companies marched a dragnet across the central highlands, daring the NVA to put up a fight in broad daylight! The 199th Light could rely on almost instantaneous artillery and CAS support when in battle.

And when the 199th rifle company stopped each evening to hunker down in a temporary, nighttime defensive perimeter (NDP), they marked a landing zone (LZ) for the helicopters. Pallets of rucksacks, body armor, mortars and recoilless rifles came in with extra ammunition, batteries, medical supplies, meals and water, plus sandbags, lumber and spools of concertina wire. Yes, the enemy might send an artillery barrage and assault wave against the 199th rifle company at night. But the 199th would be prepared for it.

Besides, with such incredible mobility through the jungle, the 199th Light could match or even outpace NVA regiments. It was immeasurably difficult for the NVA to gain and maintain contact with the 199th during the daylight march. And so the sheer mobility of the light infantry rifle companies meant that they often walked beyond the range or detection of the NVA artillery!

In this manner, the rifle companies of the 199th Light used mobility to chose the time and location of their fight with the enemy. This elusiveness gave the 199th an awesome advantage in battle.

Two different approaches – the stealth of the 187th Rakkasans and the mobility of the 199th Light. Yet the rifle companies of both of these units managed to achieve elusiveness. And that spelled tactical success at the small unit level.

This article was originally published on odjournal.com (Olive Drab: the journal of tactics) and has been transferred here with permission.